The following conversation is part of an ongoing series called Memories in Exile, in which we interview current and former resident writers who have come to Pittsburgh and lived in exile on Sampsonia Way. The series is in celebration of City of Asylum/Pittsburgh’s 15th year, capturing the diverse experiences of writing and living in exile. Throughout these conversations, we explore how memory shapes writing and how the experience of memory is unique for writers who are under threat of violence and persecution. Each interview is edited in collaboration with the writer.

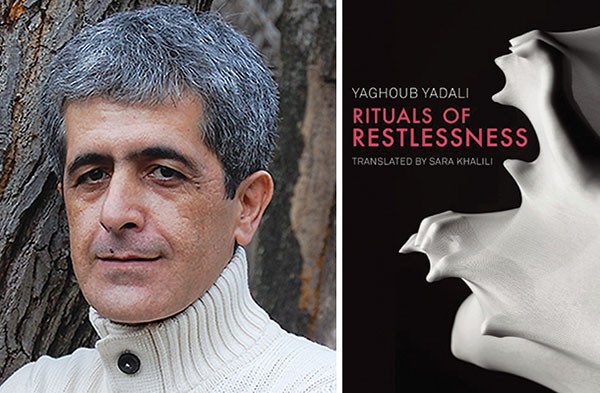

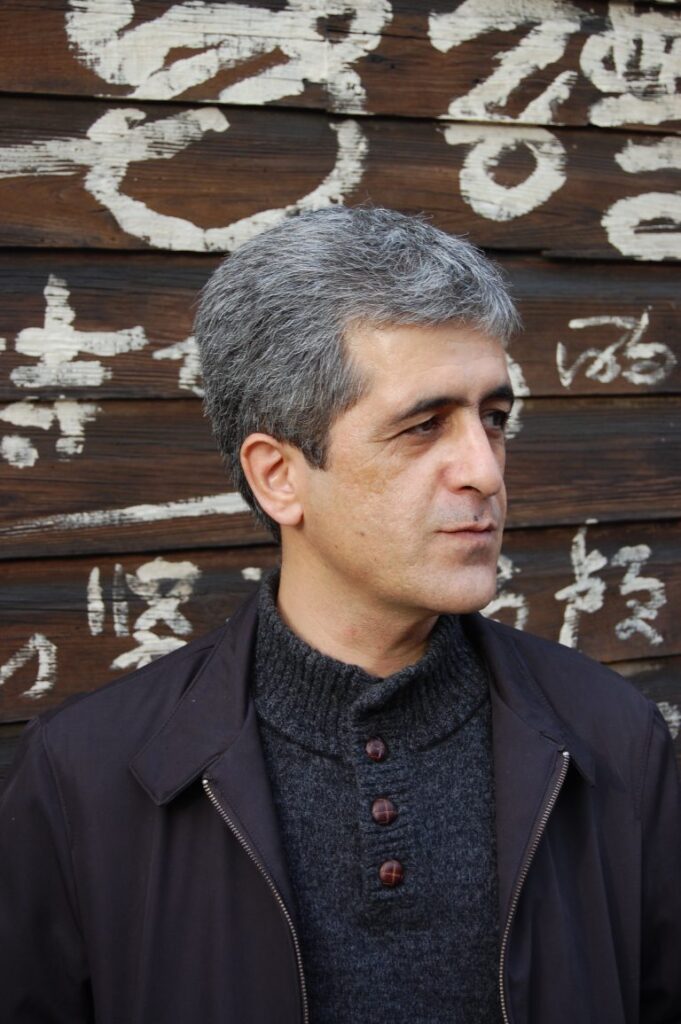

Iran native fiction writer and television director, Yaghoub Yadali, is the author of Rituals of Restlessness and several other short story collections. In 2007, Yadali was imprisoned for one year due to a complaint about an adulterous love affair in Rituals of Restlessness. He moved to Pittsburgh in 2013 for his two year writer-in-residence program at City of Asylum and now lives in Amherst, Massachusetts. Before the Exiled Voices: Resident Writer Reunion, Yadali spoke to Sampsonia Way about Iran and the role of locations and memories in his past publications.

When you arrived at City of Asylum as a writer-in-residence, what surprised you the most about living in Pittsburgh?

The first interesting thing I discovered in Pittsburgh was people’s friendly behavior. They’re much friendlier than Bostonians. I lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts for a year, and I never talked to my neighbors there. When I resided in Northside, Pittsburgh for two years, I knew most of my neighbors and had the chance to participate in local events with them. Some of them became my friends.

Once, a friend in Pittsburgh invited me to a reading at a church. I asked a question that intrigued other attendees, who gave a lot of answers in response. It was a unique experience because it was the first time I attended a reading in a religious place.

What have you been working on recently?

Currently, I’m working on a novel about immigration, and I’m doing research for another project — a historical novel. Some afternoons when I don’t need to edit or revise, I work on different projects.

I normally write in the mornings and edit and revise in the afternoons. This, along with other projects, helps me keep a distance between myself and the piece I wrote the day before. Being away from your writing for a while makes your mind ready for the next piece.

How have your experiences in traveling and your memories informed your writing?

You always use your memories and experiences to write. This year, I published a novella, which was based on my memories from when I was in prison. That experience — the imprisonment — changed my life forever. You cannot ignore such a terrible, unique experience. It forces you to pay attention to it.

Another example when I used my memory was to refer to an image of a cemetery for World War II victims. I visited the cemetery in my hometown approximately 20 or 25 years ago. A few months ago, I read an article about a topic related to World War II. Suddenly, I remembered that visit I made so long ago — that’s a connection. So, I got an idea for a novel. You’ll never know exactly how it happens — a connection between something that you’re reading in the present and something that happened so long ago.

Are there any images from your memories that have appeared in your writing more than once?

Images appear from my childhood house. Places around that house. The streets. These places are in my work in different ways, sometimes as the main location or solely in a short passage. There is a particular memory about the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s that has appeared in my work a few times. When I was 16 years old, I was going to participate in the war. My cousin, who was my best friend as well, talked to me on behalf of my father and changed my mind. At that time, everything in the country was surrounded by the terrible effects of the war. Some of my classmates in high school died in the war. We had funerals in our neighborhood every week. All of these events motivated me to write about the war. Five out of the 21 short stories I’ve written are about the consequences of this war. Although there are not any particular recurring images within the five short stories, you can find some similarities in characters, who are silent but share the same sentiment of wanting the war to be over.

How do you and your family preserve Iranian culture in America?

We cook Iranian dishes most of the time and celebrate Iranian traditional holidays. For example, we celebrate Nowruz — Iranian New Year’s Eve — on the first day of spring in our calendar, which normally is around March 21st. For Nowruz, the oldest person of every family is expected to give cash to the younger members of the family.

We celebrate the last night of fall, which we call Yalda, too. This is also known as the longest night of the year. At night, the family gets together, gives gifts to one another, and has fun while eating watermelons and pomegranates, which are the traditional fruits for Yalda.

There is also the Ceremony of Wednesday before Nowruz that I like a lot. It’s a celebration everybody in the neighborhood can participate in. At sunset, people make small bonfires, jump over the flames, and sing a verse that translates to “Let your ruddiness be mine, my paleness yours.” It’s a symbolic event that represents sharing happiness and throwing away problems with sympathy and understanding for one another.

What are your thoughts on censorship in Iran?

In Iran, you have to send your book to the Ministry of Culture to get permission to publish it. So that’s a complicated process — getting permission. I always say that there are three sorts of censorship in Iran: the first is official censorship, the second one is self-censorship, and the third is communal or societal censorship. Sometimes, the second and third ones combine.

For the case that resulted in my imprisonment, the person who made the complaint against my novel was from a local minority community, not the government. So, for my next novel, the case was on my mind, and I thought, “Oh, I should be careful about each word I’m writing because of that minority group, that part of the country, and different groups in the country.” This is a sort of censorship, which can become self-censorship. Self-censorship can especially happen when you write about politics. I try to ignore censorship when I write, but when I edit and revise in the final steps, I face a dilemma. Do I remove the controversial words and sentences to get permission for publication or keep these words and sentences? This, unfortunately, may conclude with an unpublished work in the corner of my computer.