Interview by Timmy Miller and Thia Paruchuru

The following conversation is part of an ongoing series called Memories in Exile, in which we interview current and former resident writers who have come to Pittsburgh and lived in exile on Sampsonia Way. The series is in celebration of City of Asylum/Pittsburgh’s 15th year, capturing the diverse experiences of writing and living in exile. Throughout these conversations, we explore how memory shapes writing and how the experience of memory is unique for writers who are under threat of violence and persecution. Each interview is edited in collaboration with the writer. In this interview, Huang Xiang’s answers were translated by Zhang Ling and Natalie Ing.

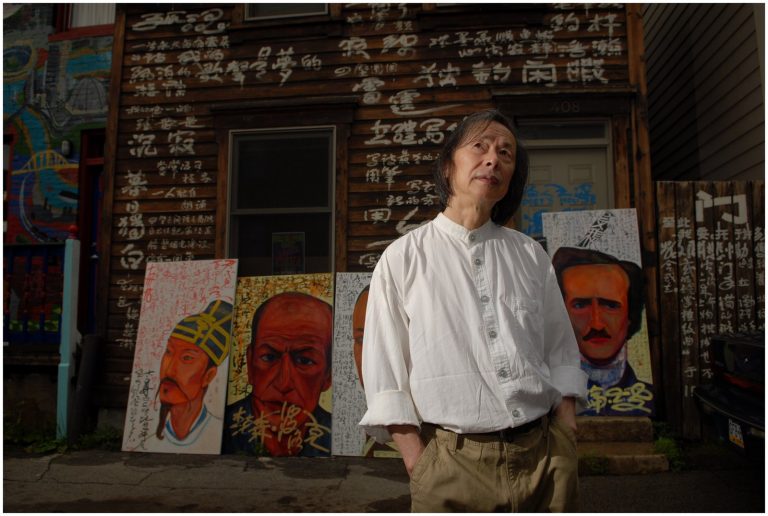

Huang Xiang was the first writer-in-residence for City of Asylum/Pittsburgh, living on Sampsonia Way from 2004 to 2006. Born in China, Xiang quickly became known as a revolutionary poet who often spoke against China’s communist regime. He was incarcerated numerous times and often abused in prison. The controversy surrounding his works, which have been banned in China from as early as 1979, has never discouraged him from producing poetry. He has written and published numerous collections, which have been translated for audiences worldwide, including The Thunder of Deep Thought: House of the Sun Notebooks, Number Two. Today, Xiang lives in New York City with his wife, Zhang Ling, and still actively writes.

It’s been more than 20 years since you’ve been back to China. What do you remember most from your time there? And then, what do you remember most about first coming to the United States?

Huang Xiang: My most vivid memory from China comes from when I was younger. I remember the freedom that I had as a child, and my family. And then when I came to Pittsburgh, I felt the freedom of speech. Back home, I felt like I was being trapped. Coming here, I felt like I was released from a cage. Not just a cage, but like I was a stone buried in the ground. When I came to America, that stone exploded and my spirit was released. Back in China, everyone is restricted — but not me. My spirit is like a black hole that absorbs everything that is happening around me. I am free.

Did coming to the United States change your creative process?

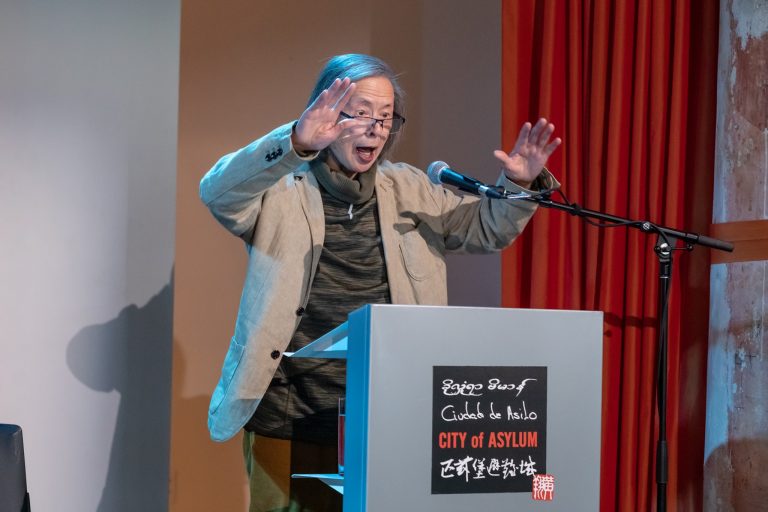

Huang Xiang: In my youth, I wrote about the universe and the planets and the deep thunderstorm of thought. Coming to the City of Asylum, I emerged from that darkness. It was like a curtain was opened. People could see me. And I could see how there are barriers in language, but writing can help us express ourselves. I wanted to explore this through the universe of poetry outside of the human body. There is a spiritual expression as well as physical expression. Languages can not only explore humanity, but can express even more than religious teachings. Language is so expansive that it is all across the universe. Without any time constraint, people can relate to it in the past, present, and future.

You were imprisoned in China for many years. How did you cope with that obstacle to your creative expression?

Huang Xiang: In the prison, it was really cold. I only had a blanket and a torchlight to do my writing. In the daytime, I could not do anything. I could only draw and write poetry at night. My mind could not be limited, though. The guards would shine a torchlight into my room and ask me why I was not sleeping, and I replied, “It’s me, Huang Xiang! I am writing.” I just wanted to express my soul.

And that changed when you came to the United States?

Huang Xiang: When I first came here, I always wondered why people’s thinking and opinions were being recognized throughout the world. Coming here, I didn’t have to worry about people barging into my house. I didn’t have to worry about being restricted or being controlled. The freedom here is very eye-opening. When I came to Pittsburgh, my heart drew constellations. I have been to many places, where I was exposed to different cultures and different civilizations. I think City of Asylum does a great job to help writers from different countries. Here, I can open the curtain to find the human spirit, and I hope others can contribute to the spiritual society, too.

Looking back at these experiences, both from China and your time at City of Asylum, how have these memories helped you to create your artwork?

Let me answer this question. Memory is very beautiful. I think it is important for the exiled writer. Every time we think about Pittsburgh, our hearts feel so warm. It is like our home country. When we came back and saw Sampsonia Way and the new building and the people, it was like we came back to our hometown.

So, for both of you, it must feel great to be back in Pittsburgh.

Zhang Ling: We missed this: people enjoying and appreciating his artwork. People liked his calligraphy, his writing, his poetry, which inspired him to continue to write, because in China, all of his literature and art is banned. Chinese society doesn’t know him. The government said he was a dangerous person, and they kept students far away from him, so his work could never be appreciated. When we first came here, a scholar asked him, “How could you keep your confidence, since your artwork could not be published for many years? How can you believe that your work would be loved by people?” He said that it is spiritual for him — that after his life, society may continue to read his work. Even though he is banned in China, he doesn’t care about the government and continues to create works. Here, society and the city, they like him. They like his story, his poetry, and enjoy his calligraphy like art. It inspired him. It saved him. It kept his spiritual confidence to continue creating.