The Cuban author shares his journey as a dissident.

This story is published in collaboration with our news partner Pittsburgh Latino Magazine.

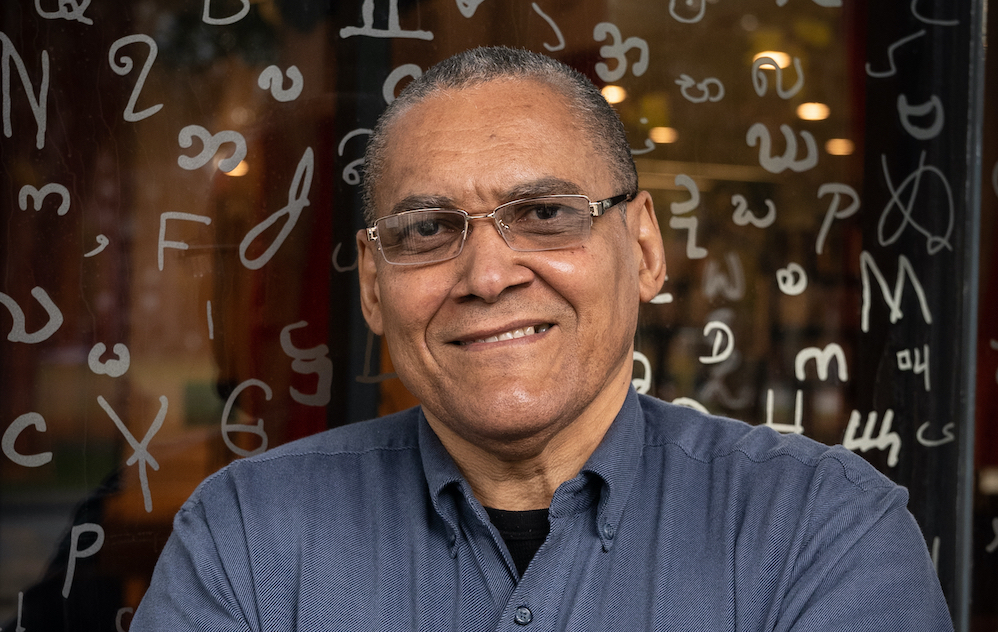

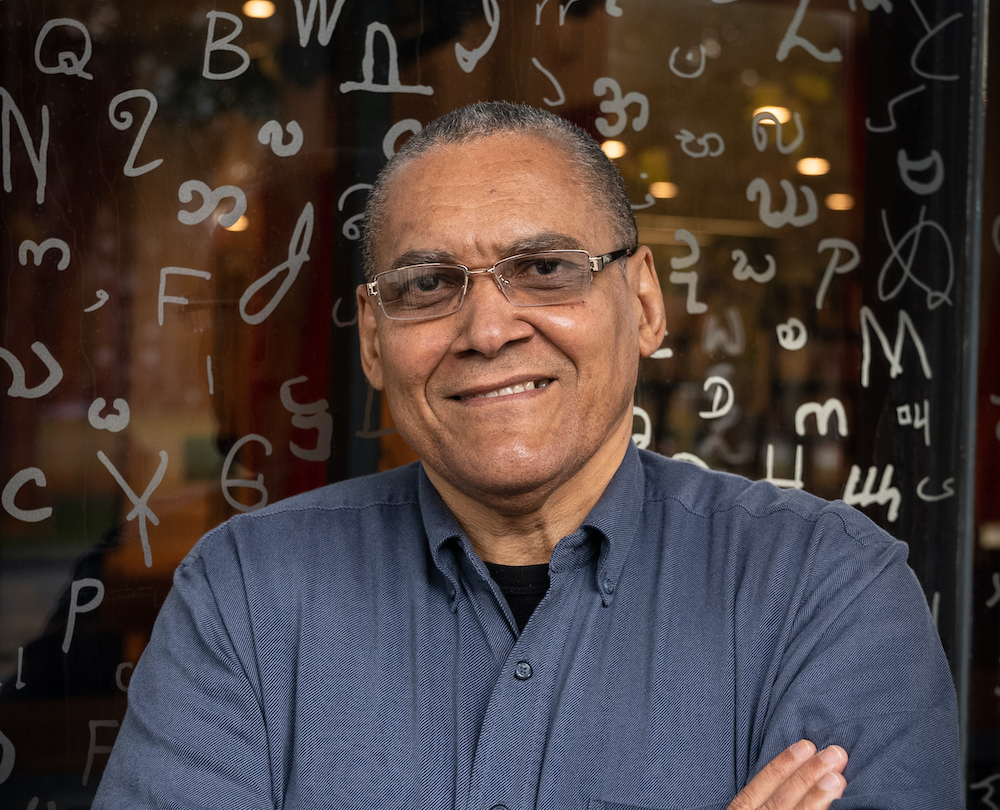

Jorge Olivera Castillo is a Cuban poet, writer, television editor, journalist, and songwriter. In Cuba, he became a known dissident and fervent advocate for freedom of expression — ultimately leading to his incarceration in Guantanamo. Olivera Castillo has published six books of poetry and two short story collections. His works have been translated into several languages, including Czech, English, Italian, and Polish. His two most recent books — Antes Que Amanezca y Otros Relatos and a poetry collection Quemar las naves — are based on his experiences as a soldier in the African jungle during the Angolan Civil War.

And it’s safe to say that despite the many obstacles and hardships that Olivera Castillo has faced, he stands resilient and is continuing to push literary boundaries. The poems that he has shared for “The Everyday Pandemic” certainly express as much. We are so grateful for his contributions and consider ourselves lucky to have Olivera Castillo as a part of our Pittsburgh community.

In the following conversation, Sampsonia Way had the opportunity to sit down and to talk about his experiences as a dissident, his experiences here in Pittsburgh as an exiled writer, and how the pandemic shaped him and his writing.

To get started, we’re wondering if you could introduce yourself and tell us a little about where you’re from?

I’m a native of Cuba, the largest island in the Caribbean which is ruled by a dictatorship that first came to power 63 years ago. I grew up in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the capital of Havana with my four brothers. And then, well, I grew up. I studied. I became a telecommunications technician. And at 19, I went to fulfill military service in the Angolan Civil War and served from 1981 until 1983 in Angola’s jungle.

When I came back, I took a course and started working as an editor for the official television for ten years. My experience here resulted in a gradual process of disenchantment in relation to media censorship and the rest of the cultural institutions — to which I would add the complex situation of scarcity and rationing, caused by excessive bureaucracy, the absolute control over the means of production by the communist party and the impact of the United States embargo. I realized that the fundamental causes of the disaster were internal, that is, as a consequence of policies that favor equality in a poverty that generates disillusionment and drives the desire to leave the country.

Later, I became a dissident, as they call it. For me, dissidents are people who oppose the system to some extent and try to change it by peaceful means. I was always a defender of free speech. But by 1993 I was a dissident with an uncovered face. I helped begin an independent union, a small organization that was dedicated to defending the rights of workers and different independent press agencies. Despite the persecution and harassment we faced, we tried to break the wall of the official monopoly on information. After two years working for this union, I joined Havana Press as an independent journalist… and later became a writer.

But the reason I went to political prison was for running a small independent press agency called Havana Press. This involved a gradual series of reprisals that included multiple arrests, fines, interrogations, acts of repudiation by vigilante groups, supervision by government entities. At the time of my arrest, I was the director of Havana Press. In 2003, I was sentenced to eighteen years of deprivation of liberty for alleged subversive activities and sent to Guantanamo Bay. This is where my writing truly began.

And this — indirectly — is what’s led you here to find asylum in Pittsburgh, right?

Right. I was in Guantanamo prison, on the Cuban side. Guantanamo is a terrible prison, a high security prison, una cárcel de mayor rigor, as they call it the Cuban prison slang. I was in three different prisons, but most of the time I was held in the Guantanamo Provincial Prison– more than 900 kilometers from the capital. That was an additional torture.

When I was there, I had nine months in a solitary cell, in really subhuman conditions. I was deprived of sunlight that whole time. I remember that my only company was insects. It was mosquitoes, wasps, lizards, and frogs in the food. It was regularly rotten food. And both the water I drank and the water I had to bathe in were mixed with mud, with earth. So, it was a very difficult period. I got sick, obviously. I was also already coming with problems from the Angolan War. In Angola, I was twice on the verge of death by the time I was 19 years old.

I could only see my lawyer seven to eight minutes before the oral hearing, but at the sentencing, I still had not seen my lawyer. I repeat, seven to eight minutes before the trial begins. Fortunately, my relatives were advocating for my freedom on the streets and in different ways, and they were in contact with international organizations. And because of the pressure from many of the democratic governments, mainly from the United States and from the governments of Western Europe, I am free. After two years I was free. Of course, technically, it is a probation, that is, the conviction was not annulled. As I said, I was initially sentenced to 18 years.

Thank you. I don’t have sufficient enough words to respond to your journey. It’s a very hard life, but also touching and inspiring. And as a writer myself, your experiences as a writer are so inspiring to me. We would love to hear more about your work now that you are in Pittsburgh. Would you describe your experience writing your poems for “The Everyday Pandemic” series? In particular, I’m interested in “Mar abierto.”

Look, as a human being, I believe that life is not linear. Fortunately, it is sinusoidal. Sometimes we are very low, other times very high, and there are different moods that one writes from. I also write from different experiences and moods. And as you can see, my work has a trend. The experiences that I have had to live are marked by a certain sadness, a certain melancholy. Although there are also very joyful things, and I can write about love — that feeling is universal and one of the strongest feelings — much of me, of my poetry, it’s a bit, I would say, tragic. It is a living reflection of what I have had to live through as a human being on this Earth. But I also have the ability to abstract myself, that is, to get into the skin of another person and from that perspective, look towards another point of view. I have that ability.

Anything can inspire my poetry. Poetry can inspire me. It can be a fragment of a movie. It can be a conversation or a story someone told me. I have different ways of being inspired. But usually my books have an inclination to tragic poetry, which includes politics and a little philosophizing as well.

Have you noticed that my poems have very few verses? I like to concentrate the message. And the same thing happens to me with my narrative, with my stories. My stories are very short. Three, four, five, six pages at the longest. I consider poetry to be the most difficult genre of literature. I believe that one is also born with the gift, but the gift to cultivate it must be developed and must be stimulated and constantly overcome. It is a dialectical process, it is a process one develops, it is like physical exercise — the muscle is slowly strengthened. In this case, it is an intellectual exercise, but it is the same process. And now I have a more critical spirit. I can more easily detect where the error is, how I can narrate better. It’s like an alarm that can be turned on when you’re not on the right track.

Now I have a question about how you are settling your current situation here in Pittsburgh. The pandemic has obviously been a scary and stressful time for us all. What has kept you happy and grounded during the past two years? What advice do you have to share with others struggling with feelings of isolation during this time?

Fortunately, we have technology. I’m in a developed country, here in the United States, but not everyone is as fortunate. Not everyone can have a smartphone or a computer, and the cellular data is very expensive. But my advice is that the world will not end because of this. I think that this is a parenthesis study. I am convinced that this distancing will not be eternal. And there are many mechanisms to escape, at least temporarily from this situation. And I tell you, the world is not over. Especially in this country.

That is a very positive outlook. Is there anything we haven’t talked about, that you’d like to talk about — anything else you would add?

I think that we must, especially the young people, have set goals, especially aspiring writers. Do not stop writing and do not stop reading. I really believe that the pandemic has forced us to be at home and sit in front of the computer with the opportunity to create. Don’t stop creating and do not stop writing. Literature is something that I love, something that I really love in an extraordinary way, just like music. And they are things that love me and keep me with a lot of desire to really live my life. There will be problems, but there will always be problems. There will be no shortage of problems. But through music, through literature, we have weapons to fight against all of these ups and downs that are presented in everyone’s life.

About the Series: This interview is a part of our ongoing series exploring isolation, exile, and “The Everyday Pandemic.” Throughout this series it is our hope to capture the daily toll of life through the pandemic from the perspective of writers and artists who are familiar with the experience of isolation or exile. With this in mind we’ve collected stories, poems, nonfiction essays, and digital art from writers and artists from all walks of life and from all around the globe.

Interview conducted in Spanish and translated by Alexa Katherine Will.

Additional translations provided by Marion Riley.