Have we lost the art of remembering? With the inescapable reach of digital memory and the rise of state-led censorship — as seen in Putin’s Russia — our ability to remember is in existential danger.

We can say that at the visible, cultural interface of the networked image, media is now primarily and paradoxically experienced as a nostalgic loop. Nostalgia is produced through the reproduction of the representational code, but without reference to the historical mode of its own production.

— Andrew Dewdney & Katrina Sluis,

The Networked Image in Post-Digital Culture

We hope you enjoy looking back and

sharing your memories on Facebook,

from the most recent to those long ago.

— FacebookThe black box of human memory has always been an intriguing subject, hasn’t it? Its immense power drives every facet of daily life — to recognize faces, to guide us to the office, or to dial a pin code — while never really knowing why and what exactly we remember and for which reasons we forget. For centuries the mysteries within this black box inspired philosophers, poets, and scientists to break its code — to no avail. Whether it was the romantic notions of Marcel Proust, mesmerized by intense childhood recollections, or the ambitions of Franz Gall, pioneering an ill-begotten pseudoscience, these thinkers ultimately failed to elucidate all the mysteries of human memory. Mnemosyne, it appears, is good at preserving her secrets.

And yet, not one of these thinkers could have predicted how the inner workings within the black box would now be leading an autonomous life out of it. Today, as our dependence on digital memory takes hold, our capacity to remember has diminished, leaving our senses vulnerable to manipulation and misremembering.

In the post-digital age, memory is no longer a sacred private palace one visits, reviving youth dramas, emotional victories, and lost lovers. Today, to a much greater extent, it intimates a squatted house with doors wide open and floors dotted with amnesia pits. Against the backdrop of senseless wars, toothless environmental policies, and rapid life devaluation, memory has turned into a commodity, nostalgia into a political strategy, and memorization into a rare (and unnecessary?) skill gladly now delegated to machines.

Misremembering is facilitated by the externalization of memories — a trend described by Joshua Foer in his book Moonwalking with Einstein. As Foer unpacks the history and culture of remembering, he illustrates the decline of memory with a survey conducted by researchers from Trinity Dublin College in which one-third of young Brits were unable to recite the digits to their own mobile phones. Foer writes, “With our blogs and tweets, digital cameras, and unlimited-gigabyte e-mail archives, participation in the online culture now means creating a trail of always present, ever searchable, unforgetting external memories that only grows as one ages.” Yes, keeping record of our lives has gotten easier. But is it an achievement to be proud of? Are we entrusting to our devices the ability to care and exercise control over our past?

In the times of Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato, a good memory was regarded as one of the most important survival skills and a sign of an intellectually developed person. Neither notes nor books were in wide use, and the memories of what one heard, experienced, or reflected upon were passed down through oral tradition as an invaluable gift from generation to generation. Until the 13th century, manuscripts served more as tools for memory consolidation than as texts designed toward their own end. Reading had yet to be considered a leisure activity, done for pleasure.

Today, the lion’s share of individual and collective memory lives outside the human body. Silicon mechanisms — our phones, tablets, and laptops — do a much better job of storing memories than the lazy, unfocused brains of their carefree users. However, these devices are not solely designed to make our lives easier and to change them for the better. Our memories, as well as our screen time, are now a commodity: our attention is not only tracked but sold. In the so-called “attention economy,” a concept theorized by psychologist and economist Herbert A. Simon in the 1990s, the user’s focus on a particular item of information is viewed as a resource — a means to bring its supplier income. Capitalism is not interested in encouraging memorization for personal benefit and instead sees it as a useless, boring skill. It is scrolling that matters most.

Our growing reluctance to exercise memory and the sense of amnesia that follows is accompanied by another important change: the actual transformation of time perception. To memorize the Bible or some philosophical treatise of a less impressive size, one needed intellectual capacity, motivation, and hundreds of hours — a luxury today unthinkable. Today, these tasks appear especially unrealistic when considering the distracted quality of life online. According to attention span specialist Dr. Gloria Mark, our eyes will spend an average of 47 seconds on any one individual screen before moving on. And in Harriet Griffey’s grim assessment of our collective loss of attention for The Guardian, she unearthed a study by UK telecom regulators in which researchers discovered that people, on average, look at their phones once every 12 minutes.

This avalanche of stimuli tears at the fabric of our collective perception. According to Eric Schmidt, the former chairman of Google, we create as much information in two days as we did from the dawn of civilization up to the year 2003. Even if we did try to get back to a traditional natural memorization track, we would never be able to catch up with the exponential growth of the newly generated flow. It’s a deficit that might be best described by the French philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky who writes, “There is also a strong sense, felt in the everyday life of work and leisure, and its patterns of labour and consumption, that the time of the present is cut adrift from the past, which, combined with insecurity about the future, creates a sense of living in a perpetual present.”

This “perpetual present” is the opposite of what mindfulness experts advise us to seek when they remind us of the importance of face-to-face interactions, the value of human touch, and off-screen quality time. Lipovetsky’s perpetual present, on the other hand, is about a chemical addiction to scrolling, an impoverished attention span, and a weakened ability to operate information critically.

Moreover, the stream of information exposed to us in the worldwide “attention market” easily goes hand-in-hand with manipulative strategies used by repressive regimes to promote misremembering or forgetting. The consequences of such nationwide amnesias, as seen in the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, can be extremely dangerous and trigger narrow-mindedness, indifference, and unwillingness to deal with uncomfortable traumatic histories.

And in this regard, the following data provided by the Russia Public Opinion Research Center and the Levada Center are self-explanatory. In 2021-2022, 58 percent of Russians felt sorry about the collapse of the Soviet Union, and 56 percent fully or partly agreed that Stalin was a great leader. On the other hand, only three percent, associate the USSR with human rights violations, repressions, and totalitarianism.

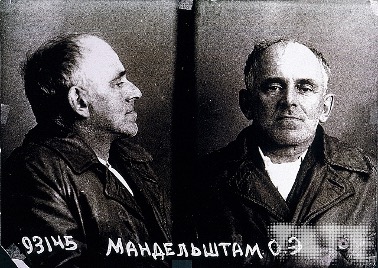

One might ask, how could citizens of Russia forget about 1.6 million compatriots killed by the regime? How could the memory of labor camps and the 18 million civilians condemned to them be erased from the minds of their neighbors?

Just as it benefits Big Tech to design devices that entice consumers to lose their capacity for memory, the manipulative mechanisms of state-sponsored censorship and propaganda serve a similar purpose. Consider, for instance, the Kremlin’s efforts to deliberately liquidate evidence of human rights atrocities during Stalin’s reign. In 2021, the Russian state outlawed and shut down Memorial, a human rights organization working since 1989 to make a transparent record of crimes by the Gulag and the KGB. The shuttering came on the heels of the arrest of historian and Memorial chairman Yuri Dmitriev, who helped publicize the names of thousands of citizens killed by Stalin’s secret police. He is perhaps best known for his work to unearth mass graves revealing thousands of forgotten deaths during the Great Terror of 1936-1938. In 2020, however, Dmitriev was imprisoned for alleged pedophilia charges, which, according to The New York Times have been widely interpreted as retaliation against one of Russia’s fiercest advocates for transparency of information.

These restrictive policies run parallel to the ongoing promotion of a national misremembering. When describing the collapse of the USSR as “the biggest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” Russian President Vladimir Putin actively promotes a positive nostalgic image of the perished empire, planting in his countrypeople an idea about a possible reunion. Under these terms, “liberating” Ukraine is positioned as one of the necessary steps to reach this goal.

In 2020, two years before Russia launched an attack on their sovereign neighbor-state, Russian historian and translator Nikolai Epple left a vivid and prophetic warning of the shifting tides of memory and the consequences of a nation living in a “double reality.” He writes: “Such uncertainty about the past, in its turn, shapes the present. The frozen and “unpredictable” history of a country with a double memory shapes a double reality in the present, which is at best fraught with inability to move forward, and at worst — an open conflict.” The case of the Russian nostalgia market, thus, clearly shows one thing: delegation of external memories, as well as non-critical overexposure to online content, make people vulnerable to tricky and manipulative moves, forcing them to misremember not only their private past but also that of their nation.

So, next time you hear a patriotic slogan promoting a nonexistent past — like “Make America great again” — just ask yourself: Was it really so great?

Olga Bubich is a Belarusian journalist, writer, photographer, and lecturer. She is based in Berlin as an ICORN Fellow — an international program that supports writers in exile.