The following conversation is part of an ongoing series called Memories in Exile, in which we interview current and former resident writers who have come to Pittsburgh and lived in exile on Sampsonia Way. The series is in celebration of City of Asylum/Pittsburgh’s 15th year, capturing the diverse experiences of writing and living in exile. Throughout these conversations, we explore how memory shapes writing and how the experience of memory is unique for writers who are under threat of violence and persecution.

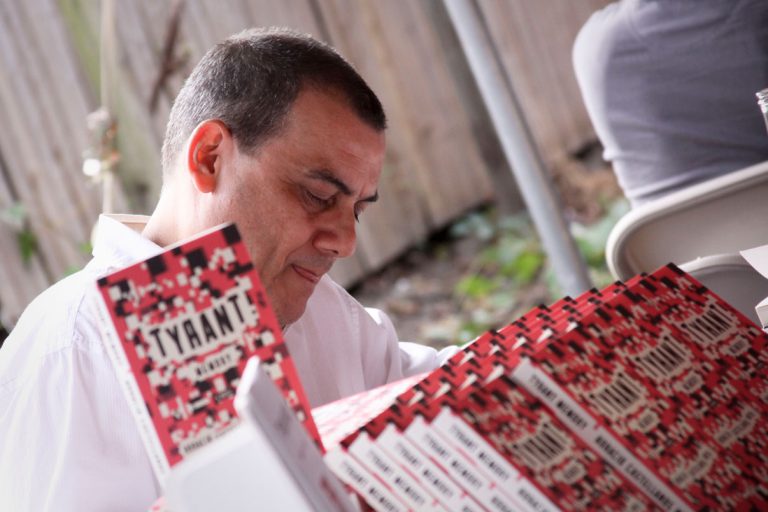

Horacio Castellanos Moya is a Salvadorian fiction author and journalist. He has written and published over a dozen short story collections, novels, and books of essays, including The She-Devil in the Mirror and The Dream of My Return. His body of works has been translated into 12 languages, including English. Alongside his time publishing nine fiction books, Moya spent two decades as a journalist in Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Venezuela. During his time at Sampsonia Way, Moya taught at the Writing Program at University of Pittsburgh. In 2009, he was a guest researcher at the University of Tokyo. Before his residency at City of Asylum from 2006 to 2011, Moya was a writer-in-residence at the Frankfurt International Book Fair from 2004 to 2006.

What have you been working on since you left City of Asylum?

Life is quite intense. To pay my bills, I teach at the University of Iowa. The university has a program that is an MFA in Spanish creative writing. I teach the fiction workshop for Spanish-speaking students who come mainly from Spain, Columbia, and Argentina. Some are starting, but many of them have already published books. They come here for two years, work as TAs, and work on their new books.

But before going to the office, I write. If I could skip the office, I would skip the office. Time is the most precious thing for a writer because, unless you are a very successful bestseller and you can get all of your income from your books, you need to get another job on the side. So what you are always looking for is time to write, right? So in this spirit, I’ve finished two novels, The Dream of My Return and Moronga. They were published in Spanish, and one in English, too. My most recent novel was published in Latin America and Spain in February of last year. That took a lot of my energy because four years to finish.

How have your experiences and your memories from home influenced your writing?

I think they are the key points for me. I think that for a writer, their childhood, youth, and maybe the first part of adult life are the raw materials for writing. Then, mainly, they’ll have enough important experiences to write about. In my sense, I grew up in a country that was very polarized in a political way. There was a huge radical excision between the fascist military and government supported by Reagan and the left. There were two armies fighting. There were 10 years of civil war. People died. And death is the most important experience for a writer. The closer you are to death, the more you understand the sense of life, right? Because you don’t think too much about what you cannot lose, right? If you assume you will always have that, you don’t think about it. But if you have the sense that life is something that — from one moment to the next — can be taken from you, then you are under a lot of pressure.

It doesn’t matter if you are involved or not in the violence, because there is death all around. The civil war? What is it about? It’s about death. It’s about killing. It’s about suffering. So if you are young, you are very sensitive. For me, those experiences were the material that went into my memory. And I am just taking it little-by-little in some books. It doesn’t matter if the book doesn’t take place right at these scenes, but I think that I am affected by them when I write. It doesn’t have to be direct. It’s not about writing nonfiction, about how I saw this, or how they killed my best friend. It’s not about that. It’s about how those impressions — the way your memory, your psychic apparatus, has been hit by life, by death — how that creates a way of seeing the war, seeing life, seeing human beings, and how that is reflected in your books.

I don’t write, let’s say, autobiographical things. My experiences of my country, my experiences of youth and childhood, they are there. They start, like a good scotch or good rum, to get older. The older they get, when they come out, they come out as fiction, they don’t come out directly as a nonfiction story.

Looking back throughout your life, and through your experiences in exile, what do you miss most about your home?

The sea… some food… friends. There is some kind of invisible thing about places and countries. In that sense, I would say there is a kind of energy. In Salvador, especially where I grew up, it is very small. It is very populated. But there is an energy. You have the feeling that it’s the center of the world, you know? That’s very, very interesting because after you spend years outside your home, you know that it is not important in the sense that the planet is huge and there are so many powers. You are a small culture, a very insignificant country. But when you are there, there is a passion! People are very passionate! These invisible parts of culture, for me, are very, very important. You cannot describe them precisely: like the way people talk, the way people express emotions to each other. If that’s where you grew up, it’s something that belongs to you. And I miss that sometimes, that freedom to say whatever I think.

You mentioned how your books are mostly written in Spanish yet some are translated into English. Who do you hope your audience to be for your literature?

That’s very tricky in my case because I grew up in a country that is very small, and it’s not a country with a big market of readers. Think about your language. I write in Spanish, so I have millions of possible readers, from Spain to the U.S. to Argentina, right? But the fact that El Salvador does not have a national book market forces me into new challenges.

I cannot write thinking of a Salvadorian reader. If you face that situation where you are a writer from a place that doesn’t have a book market, you start writing without thinking to whom you write, because you don’t even know if someone is going to publish your book. You don’t have that connection. You start to write just for you and some friends, and then the books start to grow. Maybe you are just saying, “I did what I had to do.” I had to write the story that was blocking my stomach or bothering me inside and that’s it. And after some years, you’re used to writing without thinking about who is reading. If you ask me, “Who reads your work?” my response is, “I don’t know.” It’s impossible for me to know who is reading me in French or in Norwegian or in English. Who reads me in Latin America? I don’t know. And that’s weird, but that’s the way it is.

You talked earlier about your memories about the political climate in your home country and how that has affected your writing. How would you say the memories from your time in exile have helped your writing?

I think as the older you get and as you spend more years outside of your country, you start to get a lot of influences from your surroundings. And the further away you are, in the middle of a culture that has nothing to do with your own culture, you don’t have the same goal, you don’t have the same language. Eventually, you understand a lot about your own culture, about your own country. There is a way of doing and seeing things. When you go to other cultures, at the beginning, you think that they are not influencing you too much because you are still trapped in your own memory, taking things from your memory. But then those things that you had in your memory start to mix with the new experiences.

Actually my last novel, which is not yet translated, takes place in the United States, but the characters are Salvadorians. So you can see the mixing of influences. The characters belong to the generation of the civil war, the people that came to the United States after the civil war. Some of them are here legally, some of them are not, but they are all wondering, “Why did we leave?” What’s the meaning of our fighting? What’s the meaning of our struggle? What’s the meaning of all the people, all those friends who were killed? They are not writing philosophical treatises about it because my characters are not built that way. They are just working as drivers or whatever, but it’s still this memory mixed with a new reality.

Why? Because for some countries in Latin America, and El Salvador is one of them, exile is part of our cultures. If you think about how 25 percent of the Salvadorian population lives in the U.S., you are talking about the fact that one out of every four Salvadorians are here. They cannot avoid mixing. When I was promoting my book — in Argentina or in Chile or in Columbia or in Spain — they would ask me, “Why write now about the U.S.?” Well, because we are in the U.S.! And so, all the memories come from the U.S., right? It’s in the middle of this new environment, this new culture, this new way of understanding things. So the book is about that: how people are not prepared for a new culture, how it’s difficult to assume new values, and to assume new ways of how society works, how society dominates everything. Exile happens to influence writing, especially after some years away.