The following conversation is part of an ongoing series called Memories in Exile, in which we interview current and former resident writers who have come to Pittsburgh and lived in exile on Sampsonia Way. The series is in celebration of City of Asylum/Pittsburgh’s 15th year, capturing the diverse experiences of writing and living in exile. Throughout these conversations, we explore how memory shapes writing and how the experience of memory is unique for writers who are under threat of violence and persecution. Each interview is edited in collaboration with the writer.

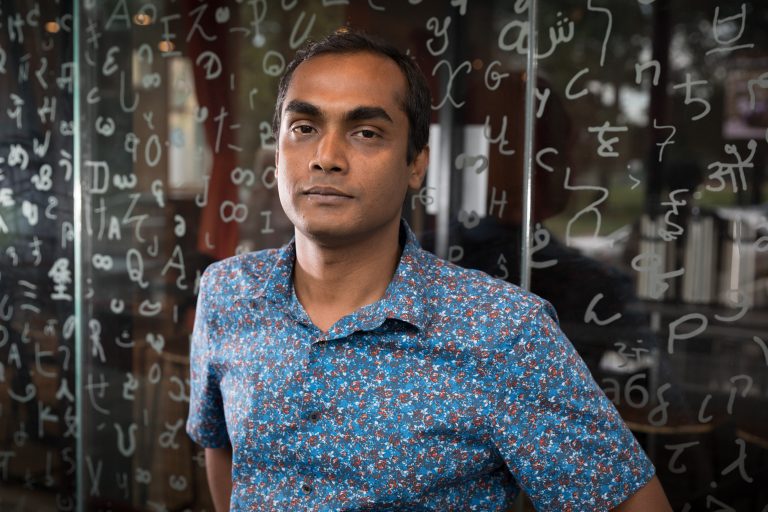

Tuhin Das is a Bengali writer from Barishal, Bangladesh currently living in Pittsburgh. Das began his career in Bangladesh as part of the resurgent little magazine movement of the 1990s, editing several literary magazines. In the last twenty years, he has published poetry criticism, short stories, and opinion columns. In 2016, his exile to the United States was spurred by threats of violence by Al Qaeda-linked extremist groups intent on limiting freedom of expression. He found refuge in Pittsburgh when Carnegie Mellon University invited him as a visiting scholar and, later, when City of Asylum invited him to join their writer sanctuary program. Das’ work appeared in The Logue Project’s Home Language, Words Without Borders, The Bare Life Review, Immigrant Report, The Offing, and Epiphany.

What do you miss most about Bangladesh?

I miss my family. I miss my parents. That’s the first thing I miss. Bangladeshi culture is totally different from American culture. In our country, parents live with their sons or daughters. That means that I feel like I am not meeting my responsibility right now because I can’t — but that is a responsibility I should be doing. After retiring, my parents built a house, and I worked on it. I was involved in all the activities, like contracting, and I planted lots of trees there. I have a connection to every corner of that land and miss that entire place. I was only able to live there for two years. I’ve been in Pittsburgh for four years. Can I call this city my home now?

How have you been able to process these senses of place and home in your writing?

I grew up in a green city, close to rivers and canals. I miss the streets there, too. Basically, in my country, I was spending a lot of time with my writer friends, just arguing with each other, and planning what was next. I was publishing poetry magazines at that time, like 42 issues of nine different magazines. I miss hanging out on the street in the evening. And also there are some buses. I would watch those bus windows on the Barishal-Dhaka highway, see where people are going, and think, Where are they coming from? Where do they go?

Recently, I have been writing about my cats, about how I miss them. I thought that they would remember me, but one day I was video calling with my mother, and I said Oh, can you show me my cat? And my mother held up the cat, and my cat, she didn’t recognize me because her brain is not like that, you know? They forget. And I realized, Oh, she doesn’t get that pain. She is okay without me. Then I felt okay. I felt relief from that pain.

Do you ever visit the rivers in Pittsburgh and think of your home?

When I first came here, I had a lot of free time. Now that I am immersed in American life I feel like I have no time. But back then, I had a lot of free time and went to the river a lot. Sometimes as early as seven in the morning. You know how you have some days, some nights, where you just can’t sleep? It would happen to me like five or six times in a year. So on those days, in the morning, I went out onto the Kirtankhola River, and I felt good. That was my thing. I would think very deeply. And on those days I understood more — I realized a lot of things that I wasn’t able to realize before. Here, I would sit on the Allegheny River by myself, and I would think about my city, Barishal. In Bangladesh, I can jump and swim. Here, I feel like I can’t do that, so that is another thing I miss.

When you first arrived at City of Asylum was there anything that surprised you about Pittsburgh or America?

I was surprised — surprised in a good way — that I was getting all kinds of support from City of Asylum. I got housing. I got a stipend for living. I got any medical assistance I needed, and legal assistance for immigration things or taxes. It surprised me that someone could help me in this way. I didn’t expect that. It is a nice community.

Food was difficult for me. Food was a big cultural shock. I was going to a lot of Indian grocery shops in Pittsburgh, but after one or two years here, I am more used to the food. I totally quit drinking coffee and tea. I miss that taste of my country, and I don’t want to change that with American coffees and teas. That is a memory I want to keep alive.

How does a sense of memory influence your writing?

After coming here, I have been working less on abstract writing and more in documenting my reality, past and present. I have been writing more memoir. I’ve wanted to write more about my home city, my river, and my childhood. I am feeling more interested now in writing prose about my personal feelings. I began, for instance, to write about my childhood and my childhood perception of discovery and wonder. I wrote about grade school, and how I grew up living in an apartment building, and until a certain age I barely ever left that building. In my writing, I describe how one day I found that there was a small market in front of our building. From our rooftop and from out our windows I began seeing people coming and going. I thought, Who are they? Eventually, I went down to the street and I talked with the people in the market. At first, I visited one street, and I went back inside. The next time I came down I went through three or four streets. Day-by-day, I went through each of these markets and streets. Through this process, I found my outside world. I saw that this is a street, that is an intersection, and that intersection went three or four more directions. And then I got excited. Now where can I go? There are more things happening, there are more people.

It was a thirst for knowledge, new experiences, and the unknown. I was thirsty for what was next. I would see people and think, Who are they? Who are their families? Where are they living? Are there more people? And then I would see, Oh, this is a country. Here is a city. There is a village. There are more countries. I’ve become interested in how everyone’s “personal” is a whole different world. Maybe it will be a book? Or not. Time will tell.

How did you discover that you wanted to become a writer?

I started writing when I was only 16 years old. I was a kid, basically. I published my first magazine at only 17 years old. I also did other things, like I played cricket one year. I was flying kites another year. My generation was well connected to nature. I did everything that a kid in Bangladesh does, but I didn’t feel interested — not like I felt when writing. At the end of the day, I feel that we are all lonely somehow. My one poem says, ”Everyone has a personal form of alienation.” Writing was a refuge to me. It was a sanctuary. And I feel I brought that sanctuary with me to the City of Asylum. When I write, I feel I get some kind of shade or shadow, and by writing through my worries, I feel more free. I feel that this is my space, that I can write freely now.

You are working memoirs and essays now. But you’ve written poems and stories too. How do you identify your writing in terms of genre?

I want to create a beautiful world that doesn’t exist today. There is a lot of fighting in this world. There are bloodbaths, wars, and dishonesty, a lot of selfish people, and cruel-hearted humans. I feel bad when I see that there are so many people in the world, in my country, and everywhere — being discriminated against, disenfranchised, persecuted. And when I see these things, I feel bad and then I feel like I have to make something, like an art piece, and I try to share it with my readers.

Do you think we are born as creators? Or is this something you come into over time?

In our country, our philosophy is different. We have different views of literature, and we have different views of becoming a writer. One day, my mother said something to me because I was depressed. I was asking myself, What am I doing with my writing? Maybe people are not understanding it. Does my writing matter? My mother said to me, “It is easy to become a doctor or an engineer because you can study a book. But no one can be a writer that way.”

I believe that a writer is born. I strongly believe that idea. What does that mean? It means I grew up on that land. My mother gave birth to me, and I felt that I am here: in this air, in this water, in this land, in this soil of my country. I feel that, and I feel everything through the art. I feel there is a world outside of our body and another world inside us. We are just made by muscles, hair, cells — all of this — we are left human at last.

I feel that the creative process and what I still am doing — I’m not writing as a hobby or a way to get glory. Writing is one of my survival techniques. For me, writing is very painful, and it’s hard work. And working to get my writing translated is difficult. Producing work in exile is taxing.

But I feel it is very important to share my freethinking, and my point of view. It is important to write that. Some writers are like that.