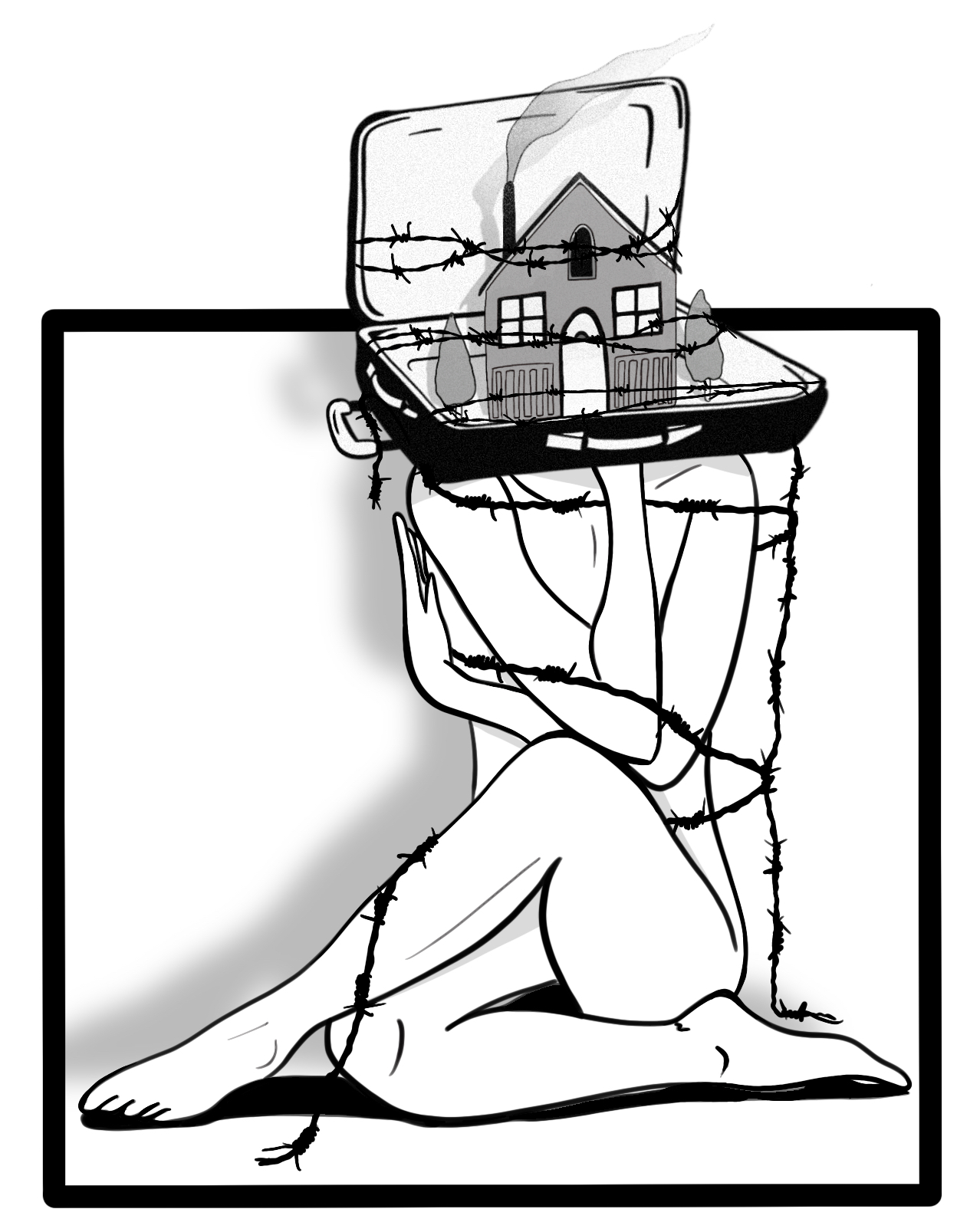

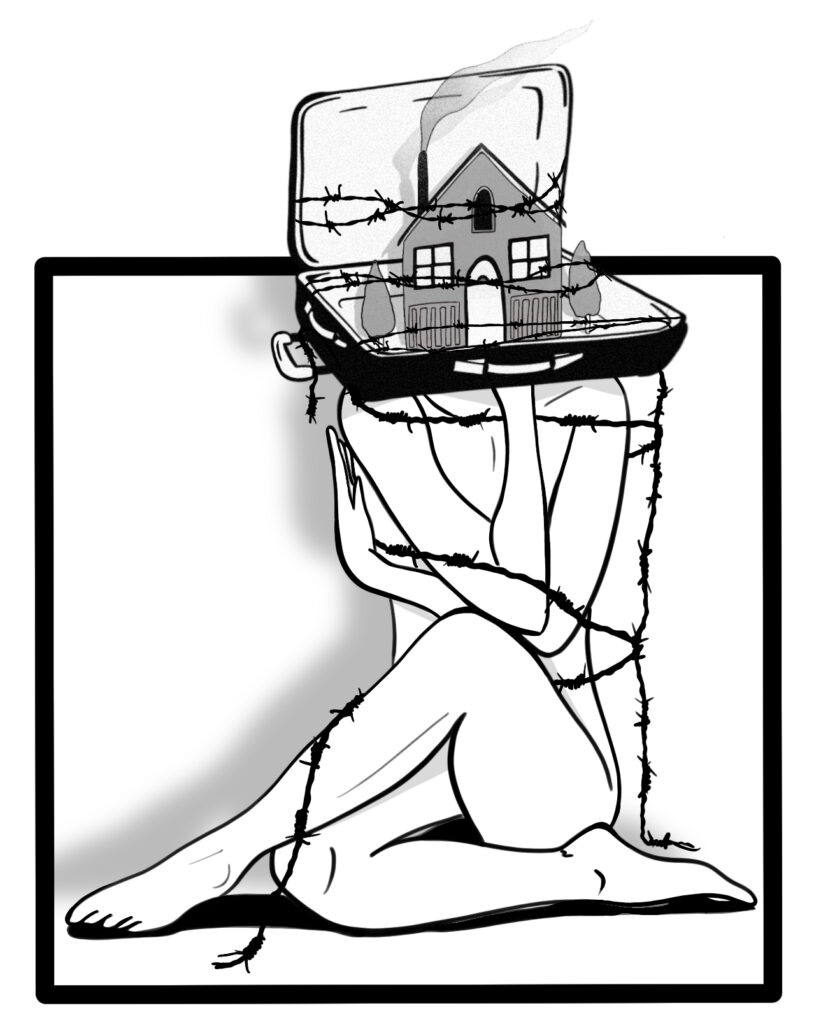

When we acknowledge the enclosures around our social and emotional lives, we get to reimagine a world without limits.

When I lived abroad, finding asylum in places like Pittsburgh and Ithaca and in Ottawa, I was repeatedly asked how I felt about exiting my country. And I had to get used to this question — for I have never related to the land as my country: it is the country, the patre — memleket. Perhaps because I tend to abstractions, or perhaps because I am so much into things-as-they-are, I could never give credence to the belief of owning land, possessing land, of making the land my own, my property.

So here is one reply: If exiting means leaving behind, then, for sure, I have not exited the country where I was born — at least not on a plane, not by traveling overseas. Claiming the land is not merely a matter of physical boundaries; it is much more a matter of how we relate to the land, what we make of it, what we make of ourselves in imagining the land.

Yet, there are human dynamics that hinder the imagination. The modern world is a world of accumulation, an accretion of capital, of property, of wealth, of matter in space. And it’s a world of motion and mobility, of social, economic, and physical tractability, largely framed by the neoliberal order. Here, in the neoliberal order of things mobility/motion are defined in terms of market flexibility. This permeates into the material reality of human bodies, and the abstraction is further attributed to reason, to our relation with the physical spaces, and to our destructive relationship with nature. Speed is never satisfactory; our capacities are contingent; we perceive threats over and over again — and none of this is idiosyncratic; it is not about personal and individual problems. These are the dynamics that define the modern twenty-first century and the rise of the neoliberal subject.

Engin Işın, a professor of politics at The Open University in the United Kingdom, characterizes the neoliberal citizen as a neurotic subject — one whose lack of self-confidence coupled with anxiety, dissatisfaction, and the idea of being under constant threat, lead to the neurotic state of being. The neoliberal subject — the neurotic subject — is the new bourgeois subject. According to Işın, the neurotic subject “is one whose anxieties and insecurities are objects of government not in order to cure or eliminate such states but to manage them.” In the past, the bourgeois subject demanded the right to property as a most sacred claim. Now, their demands are related more to their neurotic precarity within the hierarchical order. The subject lives on the edges of capital accumulation, striving for security of aesthetics and ethics. They are prompted to reach for a target that is almost impossible to reach. The target is itself elusive. Hence, they live in constant anxiety. And thus comes the state to the rescue: We are all at risk!

Today, Jean Jacques Rousseau’s approach to the birth of private property still counts for the claims to ownership over the fields, houses/homes, streets, neighborhoods, cities, states and countries. The society and polity that Rousseau wrote about is long overdue. As the pessimistic observer of modern societies, and ever-more pessimistic critic of modern knowledge, Rousseau points at the absurdity of the private ownership of land: “The first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe he was the real founder of civil society.” Thus, the bourgeoisie claims the whole of civil society, implicating the reign of inequality. Rousseau adds: “…Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.”

Yet today, we continue to ascribe to symbolic and working enclosures in our relations with space, land, and nature. We construct just for ourselves; we produce just for ourselves; we destroy buildings capriciously; we burn products. Our lives ridicule being on this earth. And we ridicule ourselves by getting into the vicious cycle of targeting the unattainable, locking ourselves into the neurotic subjecthood.

Neoliberal flexibility and mobility contradict the established boundaries of the modern state. Yet, this contradiction feeds into the increasing uncertainty, insecurity, and the futile search for homes by underprivileged people all around the globe. Those who claim the property of the lands do so in relation to honor — foreign masses flowing into their lands are threats to their honor. Property is honor; honor is property.

So where, then, do we find home?

The lands on which we are coincidentally born are the lands that define the earth itself. We presume that we leave our marks on this earth by enclosing the lands. We presume to have the natural right to own lands just by the mere act of putting fences and wires around a piece of ground. Such a futile belief! When the enclosures shape our social and emotional lives, we turn out to be prisoners of our own boundaries; we bypass the possibilities for a world without borders, limits — a world where the lands are for all, for the public. We miss out on the possibility of a world beyond the house, a world beyond fences and wires.

Exile is the proof that the land, water, and air do not belong to humans; they belong to the earth. As if we can pull the distance closer, as the exiles-as-newcomers, and the longer-term inhabitants get to the point of walking together and as they persist in doing so, we approximate to hope.

To exit is not only a matter of physical and geographical relocation. It involves symbols, emotions, ways of thinking about past-present and lesser future. It involves shifts in identities. It signifies moments in one’s life, a new phase of experiences, witnessing, and a new start. To exit reveals the plurality of homes one has on this earth. It is sorrow. It is hope. As is life itself.

This essay is the second in a three-part series titled “On Exiting” in which Simten Coşar explores how the term “exile” — as a concept and lived reality — defines the intricate encounters between one’s relation to herself and to the other selves, to selves other than herself, to institutions, to countries, and to peoples. Exile, she posits, starts, unfolds, and pauses with the questions of home, places of safety and security, moments of belonging, and a history of belongingness.

Simten Coşar is a peace academic in love with the Mediterranean. She is a former Scholar-at-Risk and a Visiting Professor at the University of Pittsburgh and has published on politics in Turkey, intellectual history, feminist politics and feminist theory in Turkish and in English. Today, from her home in Turkey, she conducts research on feminist encounters in the neoliberal academia and is the founding editor of Feminist Asylum.

Illustration by Waad Aljurayyad (@waadeid)