Tuhin Das discusses the craft of his newest House Publication on Sampsonia Way — and celebrates the release of his first English-language book.

In November 2021, Bangladeshi writer Tuhin Das completed the design of his own House Publication — which he’s titled “Comma House” — joining the impressive group of murals that adorn the homes of artist residences on Sampsonia Way. The House Publication series was inspired by Huang Xiang who painted his mural “House Poem” in 2004. As other writers-in-residence have added to the series, it’s grown into an eclectic collection of artwork and literature lighting up the hidden street tucked into Pittsburgh’s Northside neighborhood.

Das is a poet, activist, political columnist, short story writer, and essayist. His work is widely published in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India. He is the author of eight poetry books in his native language, and his debut book in the United States Exile Poems: In the Labyrinth of Homesickness was released on April 26 by Bridge & Tunnel Books.

With his mural, Das became the fourth artist to complete a House Publication on Sampsonia Way. As you come upon it, “Comma House” appears as an unforgettable burst of color — a vibrant green dotted with the 50 Bengali letters and numbers. It features a colossal comma shaped by poetry written by Das. The mural speaks volumes about its creator’s journey through life as a Bangladeshi immigrant, his fight for freedom of expression, and his devotion to his mother tongue. To learn a little more, we sat down with Das to discuss the process of designing his house.

We want to know all about the mural that you’ve designed and the making of a House Publication. Can you tell us how you went about crafting your design?

At first, I was thinking I needed to create an artwork that would be beautiful and meaningful. I wanted to create something that I would like because I live in this house. I didn’t want to create something that I would not enjoy later. In my mind, I divided the facade of the house into different parts. I planned to tell as many parts of my story as I could — stories of myself, my homeland, my home language, and my life in exile in the U.S.

The green on this mural is the color of my country’s flag, the Bangladeshi flag. It represents the very fertile land of our country where, if you plant any seed, it just grows. The red represents the blood of the people who were killed in 1971 when there was a liberation war against Pakistan. At that time, Bangladesh was called East Pakistan. The war lasted nine months in which three million Bangladeshis were killed by the Pakistani army, so the red reflects that. For the base color, I used purple, which is the color of a certain kind of water lily that grows in Bangladesh. I am from Barishal, a city that is criss-crossed by rivers and canals. Water lilies of this color grow there, even in the lake where I learned to swim. It is a very evocative color for me.

Then, I started thinking about concrete poetry, a form of poetry in which the words on the page form an image. Using this concept, I formed a poem about waiting for a tough time in life to end into the shape of a comma to symbolize the connecting of people through the art along Sampsonia Way. This poem “Keeping You Waiting with a Comma” is at the center of the mural, and because of this, I chose to name the residence Comma House.

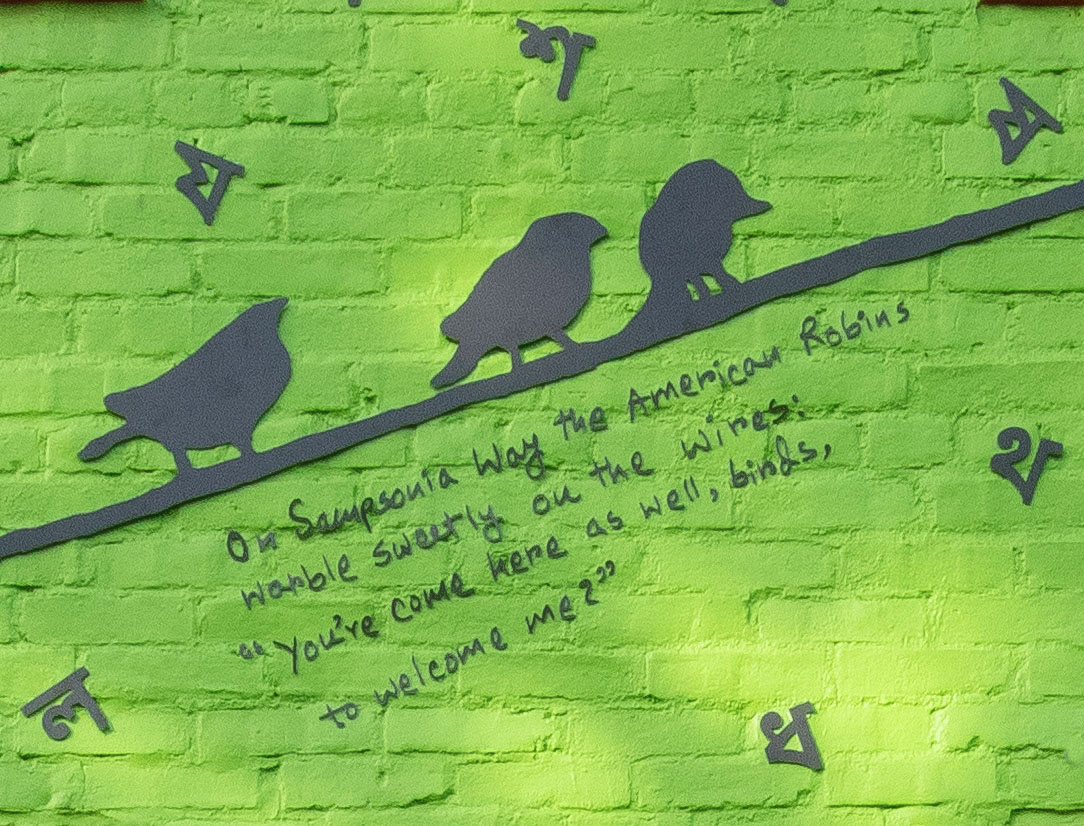

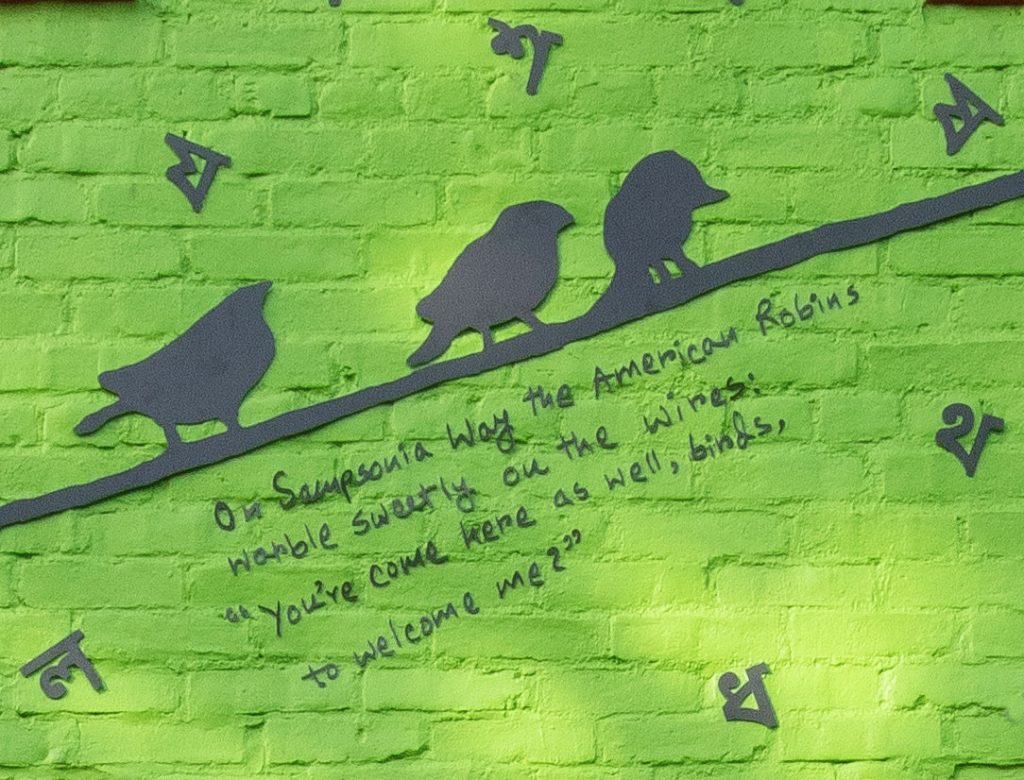

I like to create abstract pen drawings, and I specifically chose a drawing with lines resembling a face and confused eyes. With this drawing, I was channeling my pain of not being able to return home for a long time. There’s another drawing included on the mural with three robins sitting on barbed wire. When I first came here from the airport — on April 2, 2016 — and stepped out of the car, I saw three robins just sitting on a wire in front of my house. And I thought, ‘‘Oh, here are some birds. They are here to welcome me.’’ I felt like no one knew me in this distant land, and the birds seemed happy to see me. I wrote a poem about it that night in my new diary, and four lines from this poem are installed next to the birds.

I was wondering about those birds because I noticed both of the poems included on your house mention them. Do birds have a significant meaning for you?

I think birds are a special part of nature—their sweet singing early in the morning energizes me. Wouldn’t it feel great to have the freedom to fly? I wish I could fly and have the ability to go between places. Birds give me a message of hope by going somewhere. I miss the kinds of birds we have at home. There are a lot of small jungles around my town. In my childhood, I would go there and spend time climbing fruit trees, playing hide and seek with friends, and watching birds. In Bangladesh, we release pigeons and balloons as a symbol of peace to begin public events. In my surrealistic drawings, I incorporate the different shapes, including the wings of birds, and birds often appear in my poetry.

Are there any other inspirations or ideas you had for the mural?

I was also inspired to scatter Bengali letters across the mural from the other artwork around City of Asylum. I wanted to highlight the story of the Bengali language movement that occurred in 1952 in Bangladesh. The Pakistani rulers tried to forbid the official use of Bengali, suppressing my country’s mother tongue and replacing it with Urdu. Bangladeshis didn’t accept that and protested on the 21st of February, 1952. Protesters assembled in Dhaka, the capital, and the Pakistani police killed people. It became one of the greatest movements in Bangladesh and it was one of the movements that led to the liberation war of 1971.

Every February, there are cultural activities all month long to memorialize Mother Language Day in every city in Bangladesh. I grew up with this language movement’s songs, book fairs, and performances, and it continues to inspire me now. Since 2013, there have been nearly dozens of writers and activists killed by Islamic militants in Bangladesh. After 60 years of our language movement, we Bangladeshis are still fighting to protect our freedom of speech. I was trying to put together all of these truths in my mural.

Are there any other projects that you’ve done that also keep language and the memory of home alive for you?

After the pandemic started, I experienced more emotional hardships. The world stopped, and I started a new hobby: collecting stamps. The first stamp on the Bengali Language Movement was issued by the Bangladeshi government in 1972, right after independence. There are other language movement stamps issued by Bangladesh. After 1999, when UNESCO declared 21st February as International Mother Language Day, other countries recognized it as well, and they issued stamps on this topic, like Mexico, Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Qatar. On February 21 in 2008, China issued a special postmark with these words: “International Mother Language Day, Promoting Multiculturalism, Building a Harmonious World.”

Now I am preparing a catalog about it in Bengali and will translate it into English. I have a plan for an exhibition in the U.S. and I hope to give presentations about this important history. I think people can learn about not only the Bengali language movement but also these other countries, why they think this day is important to celebrate and how we can participate in this new global movement. I consider this day a global movement. Each year I can see more and more schools, colleges, universities, libraries, and free expression organizations celebrating it. I also have some ideas about how I can use these stamps as a visual art form.

And, of course, as we approach the end of April, this house poem of yours will no longer be your most recent publication, since your debut collection Exile Poems: In the Labyrinth of Homesickness is on the verge of its pub day. Can we end by hearing a little about this poetry collection? What excites you the most about bringing this new book into the world?

The upcoming Exile Poems book is my first book to be published in the U.S., so I’m excited to see how American readers will relate to its contents. In this manuscript, I use poetry as a form of activism. Through these poems I ask difficult questions, raise awareness, call for social changes, and express objections to the atmosphere of fear in Bangladesh caused by injustices committed by the state and religious persecution. I was harsh on myself to openly express and transcribe my thoughts in tandem with this disturbing reality. I always try to include challenging ideas in my writing, and sometimes people say, “Tuhin likes to work with controversial issues!’’ This is true — I don’t think we can always write about flowers, romantic love, mundane objects, and cute animals. We need to face the tyrants and discuss uncomfortable issues. Though it took six long, confusing years to complete this project, I am grateful for the many people I met during my time in exile who gave me support for this book. I want to see this book translated into different languages so my life experiences can be accessible to a wider audience.

Odessa Patmos is a Staff Writer for Sampsonia Way Magazine.