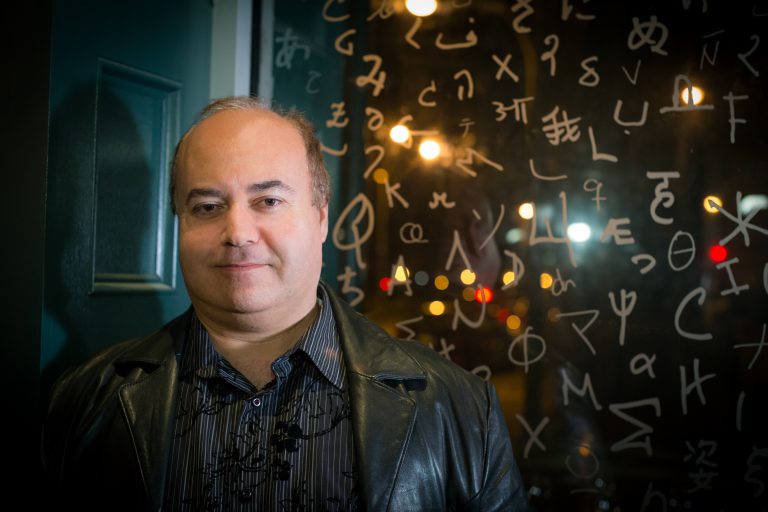

From the beginning of his career, Osama Alomar decided writing would be his identity. The Syrian novelist and poet became well known in Syria, and now in the United States, for his mastery of the Arabic al-qisa al-qasira jiddan: very short stories that are written with the speed and incision of a bullet.

Alomar describes his life just like the way he writes: short and to the point. There’s no space for a sprawling narrative. After establishing himself as a writer in pre-war Syria, he immigrated to America in 2008. Three years later, the Syrian Revolution began. From Chicago, where he was working as a cabdriver, he witnessed his country dissolve into civil war.

Despite the difficulties of his circumstances, Osama continued writing, translating, and publishing his very short stories. New Directions published his first translated collection, Fullblood Arabian in 2014. A second collection, The Teeth of the Comb, is forthcoming in April 2017.

In February 2017, Osama arrived in Pittsburgh as City of Asylum’s writer-in-residence. He is working on a new novel that takes place during the Syria’s ongoing civil war. The book will be a love story entwined with the destruction of Damascus and will follow the plight of refugees leaving the country.

Living in Syria, Leaving Syria

What was your upbringing like in Syria, and how did it nurture you as a writer?

I was raised in an intellectual family. Both of my parents were teachers. My father taught philosophy and my mother taught elementary school. I grew up surrounded by music and books. My two older brothers were poets and they played the guitar almost every day.

I was also a very boisterous kid. It’s something I inherited from my mother, who has a great sense of humor. That’s why in my stories I like to mix a sense of humor with some darker truths: black comedy.

My favorite comedian is Charlie Chaplin. Everybody recognizes him in his role as a buffoon, but I think he was a great philosopher as well–just like the writer Kafka, whose novels and short stories predicted our future. Charlie Chaplin once said that he was the most miserable man in the whole world; so it’s the most miserable man who can make us laugh this much.

Black comedy teaches us that we need to be grounded and that we also need a sense of humor to lift our spirits, to influence our lives, and balance out our psyches. Our lives look grim, but we also need rays of hope. We need something from both to establish balance in our life.

When did you become a reader, and what were the first books you started to read?

I became a serious reader at nine or ten years old. When I tried to begin reading the philosophy books from my father’s library, he told me, “It’s too early for you to read this kind of literature.” He gave me fairytales to read instead: Aesop’s fables, Arabian Nights. These books expanded my imagination, and I felt I could imagine all kinds of creatures as humans—and not only creatures, but objects, too.

That’s why in my writing, I always use anthropomorphism or personification as a tool to make projections on humans from nature, objects, and animals–especially cats.

HE SPENT MOST of his youth living a life of luxury and enjoying the blessings and the paradises of his country. He felt as if he were living in heaven. He even refused many offers of travel and work abroad. He loved everyone and felt that everyone loved him. Finally he decided to travel around the world to study the latest developments in the field of procuring ease and comfort, with the conviction that his country was without equal.

As soon as the plane took off and veered up in a wide circle, he was caught by surprise to notice that the layout of his country from the air took the shape of an army boot. Since that day, years and years have passed and his family and his friends are still looking for him everywhere…in vain.

This short story was published in the collection The Teeth of the Comb

What was your literary career like in Syria?

I studied Arabic literature at university. After I finished my degree I started publishing my poems and stories in newspapers and magazines both inside and outside Syria, in Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt. After I turned 29, I decided to publish my first collection, O Man. I knew it would be very difficult for me to get permission to publish my book inside Syria, as most of my stories are political. Even though I use metaphors in my stories, everybody could understand that they were about the Syrian government and dictatorship in general.

Other writers were very daring, much more than me, because they were very direct. They never used metaphors, and they ended up being imprisoned. Some of them were tortured. Some others fled the country. To avoid trouble, I traveled to Lebanon to publish O Man on my own expense.

At the time, the publication of O Man, my first book, was the pinnacle of my success. It felt like I had given birth to my first child. Even with that, though, the only thing I wanted was to keep writing, and keep publishing more articles, more books. Writing is my entire life. It’s something in my blood, in my soul.

In 2008 you left Syria, following your mother and brother. What events led up to your departure?

My brother left Syria first, to study medicine in Chicago. After he got citizenship, my mother followed him, and then I decided to follow her. This was in 2008, before the Civil War.

At first, I actually planned to go back and forth from the United States to Syria every two to four years. I left a lot of my writing there: my first novel, which I had finished in 2006, and several other manuscripts.

Syrian intelligence called the editor at the local newspaper that had published my short story “The Boot.” The story describes a military boot that can determine the map of an entire country. The story was included in my collection All Rights Not Reserved, and I had gotten the government’s permission to distribute the book inside Syria. I think the Syrian intelligence was very stupid because obviously they had not read the book, which was full of other stories that also were about the government and dictatorship. I also had permission for distribution.

When they called they asked the editor about this specific story. “Where is this writer, and does he still live in Syria?” To be honest with you, I was scared. I was waiting for my plane ticket, and I was all ready to leave the country anyway. I thought they would stop me before my departure but nothing happened. Once I boarded the airplane and it took off, I sighed.

What was the political climate in Syria when you left, and did you think that war was coming?

Just before I left Syria, in October 2008, the dictatorship had reached its highest peak in terms of corruption, nepotism, and censorship. Nobody could speak freely. Nobody could even think, say, or protest anything. Like many people, I thought that something would happen. But I could not have predicted it would be this much.

Black comedy teaches us that we need to be grounded and that we also need a sense of humor to lift our spirits, to influence our lives, and balance out our psyches.

How would you answer if somebody asked you to describe Syria before the civil war?

I would tell them about our great history, our many intellectuals and creatives. Syria has Zakaria Tamer, the best short story writer in the Middle East, and Mohammad Magout, who passed away a few years ago. Many people know of Adonis. There’s also the great poet Ali AlJudi.

From the new generation, there’s the young poet Shadi Sawan, who is very talented, and Fatma Naddaf, who is also very good. I have been talking with my translator, C.J., about translating some of their work into English, because they deserve it.

With my writing, I seek to resurrect some parts of Damascus’s culture: my memories with friends and memories of specific places like movie theaters and other cultural centers, my memories of attending lectures and readings. When I think about Damascus I always think about those places– the cultural centers.

My goal is to always talk about freedom of expression and human dignity, which are the most important things for me, and something that I think we are lacking in this time.

Stories as Bullets Against the Dictator

Did you choose to write in the very short story form as a reaction to the regime in Syria?

When I started writing short stories, I was thinking about dictatorship, which is another kind of slavery. Before we get rid of any dictatorship, we need to get rid of the dictator that exists inside of ourselves. To be enslaved by bad ideas is to have a dictator inside of oneself. Writing short stories helped me break this kind of internal dictatorship.

The form looks like a bullet. It’s very fast. It gives you my idea, and that is it. Nothing more. It’s the purest form of a story, and it is a very powerful form—although not necessarily the most powerful, depending on the writer.

How long does it take you to condense a story into its essence?

Sometimes it takes me one week, two weeks, three days. Sometimes it takes an entire month. Sometimes I see that it becomes not a very short story, but something in between short and very short. How this happens depends on the idea itself, which I cannot control. The idea controls me.

For example, “Historic Missile,” the first story in Fullblood Arabian, is a very short story, but it was a difficult one to write. I was thinking about history. How history can control our life, our present and our future, and I was envisioning it as a giant missile launched from the past to explode here and affect our present and future as something worse than a nuclear bomb. It took me almost a month to write that one.

Is your revision process more like erasure than adding content to a story?

It’s both. I erase a lot of my stories and my poems, and I write in slow motion. Editing is very important for me, and I always write and edit and revise at the same time. There’s no rush.

When a story is finished, I feel there is no need to add anything else. I have the sense of, “that’s it.”

Watching the Civil War Unfold from Chicago

What was it like to come to the United States and resume your writing here, in a completely different country?

It was a tipping point in my life. For the whole first year, I couldn’t write anything. I didn’t know what to do. I was desperate to find a job, any job, to make my living. I was forced to be very realistic and I couldn’t write a word. I felt as though I had become somebody else, another person.

My goal is to always talk about freedom of expression and human dignity.

After a year, I started to return, little by little, to myself. But when I started driving a cab, writing was still very difficult for me. I couldn’t go back to myself as a writer in the way that I wanted.

For the last eight years, I have been working as a cab driver seven days a week, at least 10 hours a day. Sometimes my days lasted anywhere from 11 to 13 hours, depending on the state of business. I couldn’t find a chance to keep writing as I wished. I wrote a lot, but I couldn’t focus as I wished, and I felt very far from myself, from the real Osama.

The Syrian Revolution began in 2011, while you were in Chicago. It has since turned into civil war. How did watching the situation unfold from so far away affect you?

In the first six months of the revolution, I was so optimistic. It was a real revolution against a tyrant regime. Then it became something else. Now we see a sectarian, civil war that is being fought alongside part of a revolution’s remains. The whole world is fighting inside Syria and it looks like hell.

There are over 1,500 militias, fighting each other and killing women and children. There’s ISIS on this side, the Syrian government on this side, and they are fighting each other and killing innocent people. I have become a pessimist about Syria now, and I think for anything to change it will take years and years.

Seeing the war unfold from the United States changed everything in me, psychologically. It is still unbelievable for me to understand what is going on there. Most of my writing now is about war. Even though I write about it, I think even the most talented writer or poet cannot completely describe his deepest feelings or his sadness about a big tragedy like that.

LAUNCHED FROM THE DEPTHS of history, a missile of unknown origin exploded in the present. The enormous explosion resulted in terrible loss of life and property. Shrapnel sprayed the recent past and the near future alike, leaving many dead and wounded. In the tornado of terror that spun everyone in its vortex, many thought the flames of World War III had been ignited. People rushed out to buy reseres of food and water, and took refuge in bomb shelters and basements. Scholars and historians immediately began in-depth investigations to discover the deadly historical faults from which this disaster had resulted, and the era in which they originated.

Until now their research has yielded no results. Millions of humans remain in hiding in shelters and basements, awaiting further notice.

-this short story was published in the collection Fullblood Arabian

It’s a daily tragedy to watch all of these unbelievable events happening in this century. We don’t live in the Middle Ages. After watching it, I’m sure there’s much more hatred in the world than before. I don’t know why. I wish the best for Syria, and I’m worried about the whole world.

Even though I was in the United States during the civil war, it did impact me directly. My apartment in Damascus was bombed, and I lost several manuscripts, containing short stories and poems. I also lost my novel, which I finished in 2006, and six or seven works of short fiction and poetry. They were ready to publish, too. Losing them breaks my heart, and although I cannot remember everything that was in them, I’m trying.

Before the war, almost nobody heard anything about Syria. Unfortunately, now everybody knows Syria because of the war. There are many people who understand what is going on there and they sympathize with people there, but at the same time, it’s human nature that some won’t care about it. They see Syria like it’s on another planet, very far away, and they don’t think that what is happening there is any of their business.

How did your experience of cab driving in Chicago impact your writing?

I actually couldn’t write at all about my experiences in my cab, never. I met a lot of people through that work, people of every description. All strangers who represented all of humanity. Most of them were kind, but some of them weren’t: drunk people, people who were rude for no reason. But I hated my cab, and I couldn’t write about it.

You learned that your short story collection, Fullblood Arabian, was going to be published when you received a call from your agent while you were driving your cab. How did you get your agent, and how did the publication of this book with New Directions come about?

When I arrived in Chicago I was still sending out submissions. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” and writing is my whole identity. I had decided from the beginning to establish my name as a writer, so I just kept going despite my bad circumstances.

Through Lydia Davis and my translator, C.J., several short stories of mine were published in Noon magazine. My agent called the editors and asked who I was, because she wanted to work with me. SShe is a very good agent, the same one who represents Lydia Davis. When my agent received my stories she showed them to Lydia Davis and asked her, “Can you read them? And if you like them, can you write a preface for this collection?” Lydia Davis liked them, and then my agent tried to find a publisher for the collection. She sent my manuscript everywhere and New Directions agreed to publish me. I was very lucky with them; they’re a great press.

New Directions seems to think they were lucky to find you as well, since they are publishing your full-length collection in April 2017. How has your work changed since Fullblood Arabian was published, and how does The Teeth of the Comb compare?

Most of the stories in Fullblood Arabian and The Teeth of the Comb were translated from Arabic. I wrote some of them here, but most of the stories in both books were written in Syria and translated from Arabic. The main difference is that the ones I wrote while I was in the United States are much darker because of the Syrian War.

I need to be free inside to be free outside, and free outside to be free within.

What differences have you noticed between publishing in the United States versus publishing in Syria?

In Syria, it was easier than here to publish in newspapers or magazines. It’s very difficult here to get acceptance to publish in any newspaper or magazine. I don’t know why, maybe because there’s so much competition and it’s such a big country.

The other difference I notice is that American audiences are also much more encouraging than Syrian audiences. I’m not sure why that is—maybe Americans are more enthusiastic.

What is your relationship like with your translator, and what was your process when translating these stories?

I first met C.J. in Damascus in 2006, while he was there studying Arabic. He’s my best friend first and my translator second, so we have great harmony between us. We completed most of my translations in the front seat of my cab while we were waiting for my customers. While we were translating, he was always saying, “Time is running out, time is running out, we need to keep translating! You’re going to get a customer at any second now! ”

Translating in this way was a very difficult process, but we didn’t really have a choice. I could not stay in my apartment and translate there because I would be losing money, and I had to pay my cab company $200 every week. That’s why I decided to translate in my cab.

Horizons Widen in Pittsburgh

How did you first come to Pittsburgh, and why did you decide to return?

I met the founder of City of Asylum three years ago through the PEN American center. From that meeting, I came to visit City of Asylum two or three times. A residency with City of Asylum represented peace of mind to me, a nice place to live, and where I could keep writing and return to my soul as soon as possible.

It also allowed me to continue to pursue my goals of establishing my name as a writer and my freedom. It will allow me to keep writing, to keep publishing books, and to expand my horizons through knowing more people, through gathering more life experiences. It will allow me to get more ideas so that I can write more and more.

When did you feel your soul come back?

It happened soon as I sold my cab!

You are using this residency to go back to the unpublished manuscript you lost in Damascus and rewrite the novel. What’s the novel about now, and what has the process of returning to this book been like?

My novel is partly based on memoir, but it will be about the Syrian War. As I left Syria before the war or revolution, I have to describe it from very far away, but since I always listened and watched the news everywhere I was, I can imagine and describe the events that way.

The book is a love story, mixed with the story of war: about how war impacts the relationship between two sweethearts, their families and community. Eventually the characters become refugees.

With most of my writing now, even the short stories and poems, everything is about war and about hate and love, tolerance and intolerance. I think there’s much more hatred in our world now than before.

Lastly, you said that you see Pittsburgh as helping you establish your complete freedom. What would complete freedom mean to you?

We cannot distinguish between internal and external freedom. I need to be free inside to be free outside, and free outside to be free within. We cannot be free outside and jailed inside.

Everybody can try to establish freedom, but nobody can fully reach it. There are no absolutes in life, but we need, always, to try.