The architect of “The Everyday Pandemic” talks about the complexities of isolation in the pandemic experience.

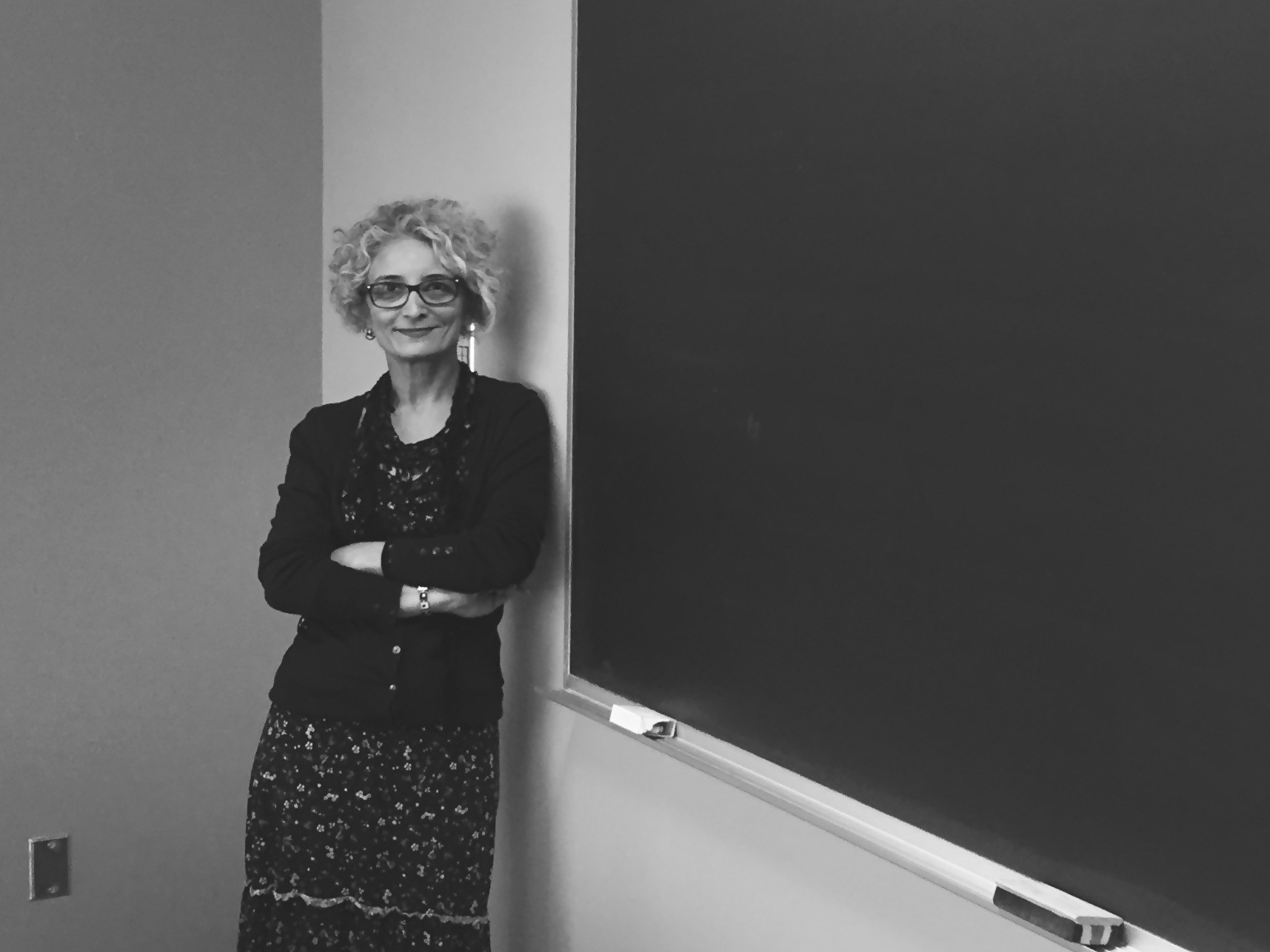

Simten Coşar is the Associate Editor of Sampsonia Way Magazine and is the architect of our newest series “The Everyday Pandemic.” She is a former Scholar-at-Risk and a Visiting Professor at the University of Pittsburgh and has published on politics in Turkey, intellectual history, feminist politics, and feminist theory in Turkish and in English. Today, from her home in Turkey, she conducts research on feminist encounters in the neoliberal academia and is the founding editor of Feminist Asylum — a feminist critical journal, forthcoming from the University of Pittsburgh Library Systems. In the English-speaking and reading world, she has co-edited two collections of scholarly essays: Universities in the Neoliberal Era: Academic Cultures and Critical Perspectives and Silent Violence: Neoliberalism, Islamist Politics and the AKP Years in Turkey. She translated major texts in social sciences from English to Turkish, and from Turkish to English. Her most recent translation is Handan Çağlayan’s seminal work, Women in the Kurdish Movement: Mothers, Comrades, Goddess.

Given your academic background — studying feminist and poltical theory — what moved you to explore isolation as a topic? And what moved you to use literature to do so?

It was mainly the daily experiences that I had been living through in the recent past that made me to consider reflecting on isolation — and certainly not within the limits of conventional political science. The turning point came when I heard someone mention how their time staying indoors was likened to imprisonment. This got me thinking. I started to come across multiple comments on social media and in other forums where individuals were expressing their discomfort with this obligation of solitude. I was — and I still am — a bit annoyed with such approaches.

First of all, not all the people had the luxury to stay at home during the worst parts of the pandemic. In the United States, we — who had to and who could stay at home — ordered our food, utensils, and the things that we wanted to buy, which, in turn, were delivered by the people who cannot stay at home. And then we had the health workers, social service providers, caretakers who had no such privilege. Not to mention that there are also the many women who face domestic violence with their shelter in place, which, of course, is not a luxury at all. So this idea of isolation as a forced obligation missed the point.

At the same time I was feeling fortunate for a couple of reasons. One, I did not have to go out in order to afford living expenses. Second, I love to stay and read and write at home, so staying at home is actually not a disadvantage for me. And from there, I can move through a long list of my good fortune. I have had no domestic violence threats in my lifetime. I have really been fortunate in that respect. Although I have been active socially and politically, the United States was always a place of relative isolation for me — since the academic culture in the country is so highly individualistic. So the isolation of the pandemic was more complex than the common narrative.

Plus, for me, I had been living with a progressive chronic illness that makes everyday life a bit of a play-setting stage. I call it a playful illness. I have to play with it because I never know what’s going to happen within every couple of hours. My planned outdoor activities are always at risk of cancellation, depending on the mood of the illness. Ironically, the pandemic made my daily plans more consistent.

So that was part of the inspiration for our series. What other perspectives are out there? For me, getting to know, understanding something, and completing a cycle of experience mostly require reading and writing about it. That is why I approached the notion of isolation with an academic curiosity, but I refrain from not limiting it to conventional political science — which mostly excludes our daily experiences as non-scientific, non-scholarly.

I think literature adds to the production of knowledge of living experiences. I have relied on literary theory and literary texts in my works on politics most of the time — because these two, literature and politics, are inseparable, especially in times of crisis, under authoritarian regimes, in transition periods when political science concepts reach their limits. As for the English reading world, I’d like to recall Gramsci’s works from prison, Machiavelli’s The Prince, Audrey Lorde’s texts, bell hooks’ texts. And then there’s Sevgi Soysal’s books and stories for Turkey. Yaşar Kemal’s books as well. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ books that account a certain historical period in South America, and especially in Colombia. And so many more. The list has too many names and countries. Let me stop here.

Throughout the pandemic how are these times of isolation and unpredictability informing your writing?

The pandemic times have brought in a continuing transition to my personal life as well as to my relation to political activism, political history, and political science. This transition had already started in 2016, but its implications took a decisive turn by the pandemic.

In 2020, it was only a month or so after I arrived at the Pitt campus when I stopped going to the campus. Actually, I really enjoyed daily communication with my colleagues and appreciated their collegiality and consideration from day one. With the shutdown, this all took on a new turn — regular meetings on Zoom are great, but they always fall short of human contact in the same physical space.

The pandemic made everyone equally accessible and inaccessible — all the friends, all the colleagues regardless of space. I believe Anthony Giddens with his emphasis on space and time contraction was proven to be universally right during this time — but of course only for those places in the world where the internet is available.

Pandemic conditions made me see that my health conditions are not fit for a full-time job that would require me to stay in the office eight hours every week day. I also became certain that in trying to live with the risk in my life, I am not tending to give into extenuating forms of risks — as in the case of temporary work.

Lastly, it helped me to balance the priorities in my everyday life — my father died of complications due to COVID-19 in our hometown. I could not go back to Turkey during his diagnosis. Worse still, I could not attend his funeral. This was hard. I did not want to risk going through the same with my mother. From the very start I have not considered asylum as a viable option for my case — which is the basic reason I spent five years avoiding residency in Turkey. I weighed my priorities, and in the end, all I value is writing freely while living a minimal life with the ones I care about. Thus, my return to Turkey last summer.

The pandemic also made me see the importance of listening to people’s individual and collective accounts in extraordinary times when official and institutional rhetoric, as well as established scientific vocabulary, fall short of explaining what is new. I started writing mostly experiential texts on my own and with friends and colleagues. The idea was already there as my ties with the universities in Turkey started to loosen since January 2016, and I have taken the first steps already as the pandemic began. But this form of writing and its fruits came out in those isolating pandemic times.

You’re writing a multi-part series about the nature of exile and how language around exile experience portrays systems of power. Would you tell us a little about your approach to this work? Especially in terms of your theoretical work?

I start with the generalized meanings of exile. How the universal vocabulary for exile is constituted, and how it is not universal, but narrow and calling for re-reading. In my writings, I tackle uncertainties and refer to the taken-for-granted facts that form the background to this vocabulary as assumptions or presumptions.

I then try to offer a counter-narrative, relying on personal and/or collective, but always daily, experiences. My theoretical standpoint has been framed within a view of critical feminist epistemology on knowledge production, mostly in political science scholarship.

Most recently I have focused on feminist interventions in academic knowledge production processes in neoliberal times. The way I try to come up with narrations on the state of feminist academic knowledge has implications in this series — I try to find a midway between the neoliberal regimes in structural terms and the way feminist academics as actors or subjects relate to these regimes in their everyday work life. I rely on the accounts of feminist academics, but I try to refrain from individualizing each and every account.

Your essay series is framed around the idea of “moments of belonging and the history of belongingness” in terms of exile and womanhood. How has the pandemic shaped these concepts?”

Tough questions indeed. If I had a full answer, then I would not be writing these columns. I try to observe, understand, and explain the experiences of the pandemic in exile as a woman — as women — by writing about certain aspects of my life with City of Asylum on Sampsonia Way between January 2020 and June 2021. In doing so, I do not only rely on my personal feelings, my personal day-to-day doings, and speech. On the contrary, I try to involve the observations and perceptions that extend to our relations with others, with the house, with the street, in online shopping, with the couriers, in the post office while sending letters to friends far away, in Zoom classes.

As for the history of belongingness — exile is not a brand new fact, neither is the pandemic. Human history has hosted Spanish Flu during the First World War and influenza in the Second World War. Both wartimes hosted plenty of exiles, forcing populations to leave places with which they had developed attachments, their families, with no papers, stripping them of their identities.

What differentiates the COVID-19 pandemic is that we are living in a world full of wars, but a world where world wars are not in currency. We are living in a world where we see that nation-states are gradually losing their monopoly in the running of global affairs, but at the same time they continue to be the sole authority on individuals’ international registries. If there is a difference in terms of our gender and national identities as well as sense of historical belongingness in this pandemic, then I’d assume that it is mostly within a continuity rather than a break with established inequalities, disproportionate risks, perhaps with differing means that perpetuate these inequalities and risks, and those by which people try to come to terms with uncertainties.

Welcome to our ongoing series exploring isolation, exile, and “The Everyday Pandemic.” Throughout this series it is our hope to capture the daily toll of life through the pandemic from the perspective of writers and artists who are familiar with the experience of isolation or exile. With this in mind we’ve collected stories, poems, nonfiction essays, and digital art from writers and artists from all walks of life and from all around the globe. The series is co-sponsored by City of Asylum/Pittsburgh, the University of Pittsburgh’s Department of English, and the Global Studies Center — and made possible by Pitt’s Engaged Scholarship Design Fellowship.

Ian Davies is a staff writer for Sampsonia Way Magazine.